Public health emergency preparedness for infectious disease ... - BMC Public Health

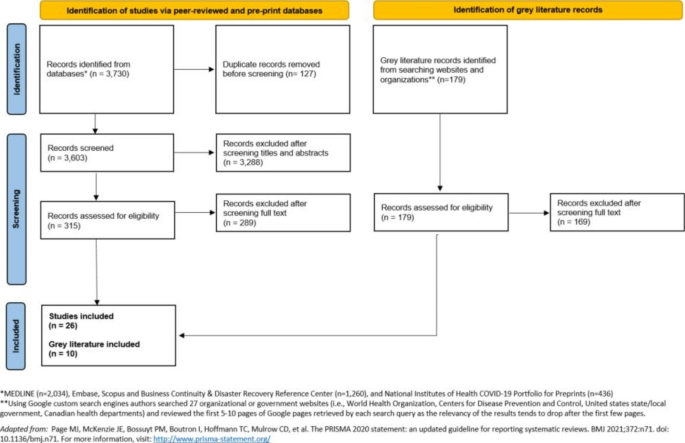

From the 3,603 records identified through the peer-reviewed and pre-print literature database searches, 315 full-text records were assessed for eligibility and 26 studies were included in this scoping review. Of the records identified from searching organizational or government databases in the grey literature search, 179 were assessed for eligibility and 10 grey literature publications were included in this scoping review (see PRISMA diagram in Fig. 1). In summary, 36 records were examined for this scoping review.

Flow chart of included records from indexed databases and grey literature searches

Characteristics of included publications

Methods and study designs varied widely across the 26 indexed literature studies, including systematic literature reviews [28,29,30], mixed-methods studies (i.e., a paper that describes a literature review, concept mapping and key informant interviews) [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46], descriptive case studies [47,48,49], qualitative studies [50, 51], a cross-sectional study [52], and a regression analysis [53]. Ten studies described a PHEP-related framework, tool or model [33,34,35,36,37, 39,40,41,42, 44], and 16 studies included content relevant to PHEP priority areas and/or activities but did not explicitly describe a PHEP framework, tool, model or set of indicators [28,29,30,31,32, 38, 43, 45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. For example, two studies specifically focused on the community engagement component of PHEP [51, 52]. All studies identified from the indexed literature described PHEP concepts for infectious disease outbreaks, pandemic influenza and/or the COVID-19 pandemic.

A total of 10 grey literature publications were identified, including four that described PHEP frameworks or conceptual models [54,55,56,57], three that described assessment tools [58,59,60], and three that focused on indicators for PHEP [61,62,63]. All ten grey literature publications described public health preparedness actions for infectious disease outbreaks, COVID-19 pandemic or zoonotic disease outbreaks. Of the ten documents identified, seven were produced by the WHO [54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. Upon identification and review of the heterogeneous evidence and guidance, we oriented this scoping review around distilling findings into high-level concepts and themes relevant to PHEP.

Elements from the Resilience Framework for PHEP that appeared in the included publications

After the first and second steps in analysis of the included studies, at least one element from the Resilience Framework for PHEP was observed in all of the identified 26 indexed studies [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53], and seven of the ten grey literature records [54,55,56,57,58,59,60], with many publications making reference to multiple elements (see Table 1). The 11 elements, listed from most to least frequently observed across the included publications, were: collaborative networks, community engagement, risk analysis, communication, planning process, governance and leadership, surveillance and monitoring, resources, workforce capacity, learning and evaluation, and practice and experience.

Emerging preparedness themes that expand on the elements in the Resilience Framework for PHEP

After comparing and contrasting as part of analysis, our synthesis resulted in the identification of ten themes that expand on the elements in the Resilience Framework for PHEP [17], all with a focus on infectious disease emergency preparedness (see Table 2). Five themes that expand on the framework were observed across both the indexed and grey literature; ordered from most to least common according to the number of publications in which they appear, these themes were: planning to mitigate inequities, building vaccination capacity, research and evidence-informed decision making, building laboratory and diagnostic system capacity, and building infection prevention and control (IPAC) capacity. There were three themes that expand on the Resilience Framework for PHEP that emerged solely from the indexed literature (climate and environmental health, public health legislation, phases of preparedness) and two that emerged solely from the grey literature (financial investment in infrastructure, and health system capacity).

Most publications described activities that should take place while planning or preparing for infectious disease emergencies to operationalize priority areas of preparedness [28,29,30,31,32, 35, 36, 38, 39, 41,42,43, 45,46,47,48,49, 51, 52, 54, 55, 58, 60]. Activities correspond with various preparedness priority areas and exemplify actions that would be taken during infectious disease emergency preparedness processes. These activities were described in publications in addition to or in place of indicators. Activities were described in a variety of ways across publications, and included steps, actions, suggestions, outcomes or outputs of infectious emergency preparedness planning processes.

Multiple studies from the indexed literature described activities related to the operationalization of preparedness [28,29,30,31,32, 35, 36, 38, 39, 41,42,43, 45,46,47,48,49, 51, 52]. For example, Jesus et al. (2021)'s model for disability-inclusiveness in pandemic preparedness provided several preparedness activities, some of which included developing intersectoral disability-inclusive pandemic preparedness, using evidence on how to reduce disability disparities to inform planning, and the reinforcement of disability-rights in health professionals' education [36]. AuYoung et al. (2022) developed general strategies for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among marginalized communities relevant to future public health emergencies [47]. Examples of AuYoung et al.'s strategies include increasing community and academic capacity to enhance community-academic partnerships, investing in trusted messengers, increasing the trustworthiness of academic institutions and developing long-term cross-site partnerships [47]. Tan et al. (2021) investigated qualitative factors related to pandemic preparedness and identified strategies to achieve a more holistic and equitable approach to preparedness [43]. According to Tan et al., the ongoing translation of changing scientific evidence into policy actions and the development of trusted communication through effective knowledge translation practices are essential strategies to achieve evidence-informed decision-making in pandemic preparedness [43]. Tan et al. also put forward suggestions related to ecological determinants of health which overlap with disaster risk reduction strategies [64, 65], including addressing the effect of health services on the environment, recognizing the impact of climate and environmental degradation on risk of zoonotic disease, and setting climate goals [43].

Several preparedness frameworks identified in the grey literature included preparedness activities, outputs or outcomes [54, 55, 58, 60]. The WHO's Strategic Preparedness, Readiness and Response Plan to End the Global COVID-19 Emergency in 2022 describes approaches to managing misinformation, such as peer-to-peer interventions to help communities identify accurate vaccine information by building resilience against misinformation [54]. The WHO's Strategic Toolkit for Assessing Risks for All-hazards Emergencies lists expected activities and outputs of applying the toolkit's six steps, one such activity is a gap analysis that can inform health and public health workforce capacity building [58]. The WHO's Risk Communication and Community Engagement tool included a list of open-ended questions intended for use within focus group discussions or key informant interviews to support preparedness planning for risk communication and community engagement [60]. Together, these activities and outputs help to operationalize priority areas of infectious disease preparedness.

Preparedness indicators

In the final step of analysis we examined studies for available indicators or actions/activities to inform indicator development. Compared to the literature identified on frameworks and priority areas for preparedness, there were comparatively fewer indexed and grey literature records identified that describe qualitative and quantitative preparedness indicators. Five indexed studies [33, 34, 37, 40, 44] and three grey literature documents [61,62,63] either included or focused on describing indicators for pandemic and infectious disease preparedness. As described in the methods, we aimed to summarize areas of preparedness measurement, rather than specific quantitative thresholds or indicators. Our focus on areas of measurement rather than specific indicators allow public health agencies to tailor these areas of measurement to their preparedness context (e.g., local, regional or provincial).

The types of infectious disease preparedness indicators identified in this scoping review measured or assessed various areas of preparedness including the equity impacts of emergencies [34, 44, 62], core public health and government capacities for emergency preparedness and response [33, 63], population and healthcare system vulnerabilities during pandemics [40], community readiness [37], and benchmarks to strengthen health systems during outbreaks [61]. Some examples of indicators related to public health and health system readiness or capacity include: adequate public health budget [62, 63], capacity to deliver vaccines and the proportion of the population getting vaccinated [33, 61, 63], licensed nurses' ability to practice in other regions or states [63], oversight of research on dangerous pathogens [61], and enhanced training for the safe transportation of biohazards [61].

Some examples of equity-related preparedness indicators identified through this review are: proportion of population in a defined region who are racialized or first-generation immigrants [34], benchmarks for public health agency plans to embed the needs of racialized or marginalized populations [62], proportion of population with access to internet and technology [44], ratio of residential and nursing homes per 10,000 population aged over 70 years old [40], proportion of population with access to clean water [63], and the proportion of households with at least one of the following: no kitchen, no plumbing, high cost of living, or overcrowded living conditions [37].

Comments

Post a Comment