Michael Osterholm: Covid-19 keeps firing 210-mph curveballs at us - CNN

Peter Bergen is CNN's national security analyst, a vice president at New America and a professor of practice at Arizona State University. He is the senior editor of the Coronavirus Daily Brief and author of the forthcoming paperback "The Cost of Chaos: The Trump Administration and the World." The opinions expressed here are his own. Read more opinion at CNN.

(CNN)After more than two years, the United States has now passed the tragic milestone of a million Covid-19-related deaths -- and the pandemic is not remotely done.

To learn more about where we are in the deadliest pandemic in American history, I spoke with Michael Osterholm, who has publicly warned of the dangers of a global pandemic for more than a decade and half and was a member of Joe Biden's Covid task force during the presidential transition. Osterholm said Covid-19 keeps firing "210-mph curveballs" at us and anyone who tries to predict what will happen in the coming months is using a crystal ball caked with 5 inches of hardened mud.

Osterholm is also the director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota and author of The New York Times bestseller "Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs." Our conversation was edited for clarity, and the views expressed are his.

BERGEN: There seems to be a big disconnect between the White House recently predicting up to 100 million cases in the fall and earlier this month the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention only making a recommendation about wearing masks on public transportation.

OSTERHOLM: Yes, I think this has been kind of a whiplash moment for the public on Covid-19. You also had the statement made recently saying that we are on the downside of the pandemic.

BERGEN: And that was by Dr. Anthony Fauci.

OSTERHOLM: Yes, his comment was obviously interpreted by most to mean that the pandemic was over. I realize that he was referring to the fact that we're out of the big peak of cases right now, which is true.

BERGEN: And he walked that statement back a day or two later.

OSTERHOLM: On the other hand, I've seen no data which supports the possibility of a fall or winter surge in the US resulting in 100 million cases. No one should make that kind of statement without providing the assumptions behind that number. Could it happen? Sure, but it's more likely if a new variant shows up that is more infectious and more likely to evade existing immune protection than Omicron. Any modeling that looks beyond 30 days out is largely based on pixie dust. I worry that the White House has gotten way ahead of their skis on this one, but I understand the administration is trying to emphasize the need for Covid relief money.

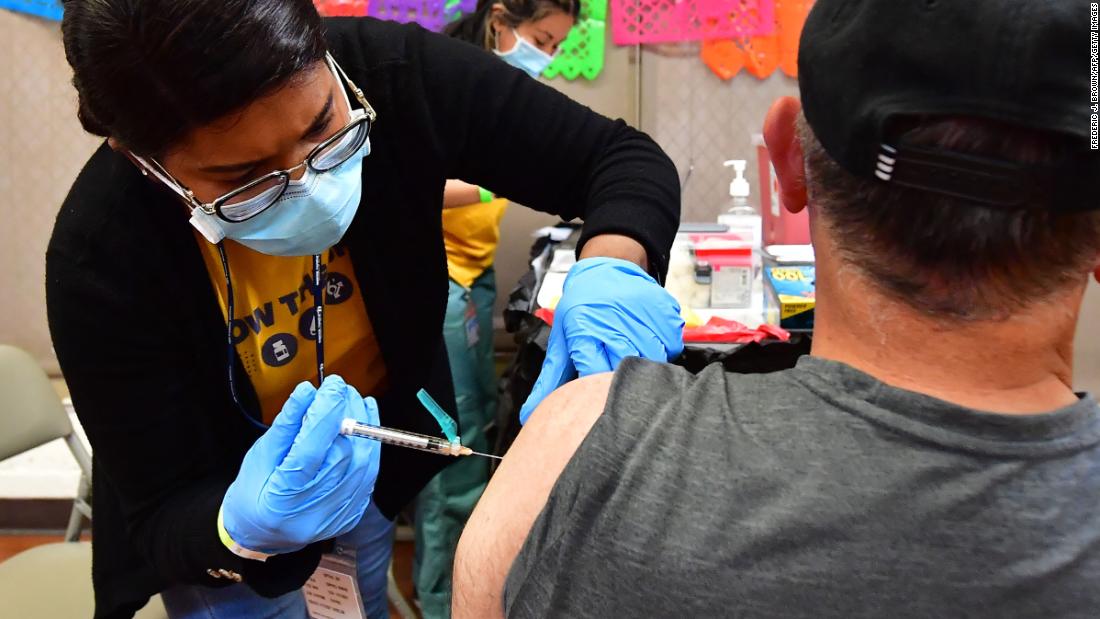

I strongly support the administration's efforts to secure the additional Covid relief money, but it needs to be used efficiently. We don't need more vaccines right now; we have plenty. What we really need is for people to get fully vaccinated. By my definition, that means at least three doses of vaccine. Only 30% of Americans have had three doses, and that number has changed little in recent months.

One of the key parts of the administration's request for additional support is the need to secure a variant-specific vaccine. But such vaccines, like the ones being developed for the subvariants of Omicron, may be less effective against any new emerging variant.

And finally, when considering what our future with this virus looks like, we must consider waning immunity protection. How long has it been since people had their last vaccination, booster or previous infection? No one knows what the impact of waning immunity will be in the months ahead. And we must have the humility and the honesty to say that.

We're currently seeing an increase in cases, but I think they are grossly underreported due to the prevalence of rapid home tests, which are largely left out of official case counts.

If you look at hospitalizations, there has been a very moderate increase so far compared with previous surges. And with deaths, the difference this time around has been even more striking. As of today, we are averaging approximately 325 Covid deaths a day in the US, according to the CDC. During the height of the Omicron surge, we saw 2,600 deaths a day, and during the Delta surge, it was around 2,000 a day, according to the CDC. This is the new phase of the pandemic. Now, with the BA.2 and BA.2.12.1 variants, there is immune protection from previous infections, previous vaccinations or both. It means there's much less severe illness, and it's not the same kind of pandemic we saw 18 to 24 months ago.

Now, the problem is that can all change tomorrow. We're still trying to understand what the emerging Omicron subvariants BA.4 and BA.5 portend. Those two subvariants have completely taken over in South Africa, and there is a major increase in cases, but they, too, are milder. And many of the cases involve people who have previously been infected. The data shows that South Africans who have both previous infections and were vaccinated likely have the best protection against BA.4 and BA.5.

I've heard people say over and over again, "This thing is as infectious as it's going to get," and yet it keeps getting more infectious. Obviously, there's a limit to that increasing infectiousness. It can't go to the speed of light, but surely, you can expect to see new variants that survive and capitalize on microbial evolution by being more infectious.

Also, the whole issue of waning immunity is really an underappreciated situation, but the key point is that we don't know what's going to happen six months from now. So, we could have 100 million cases, but on the other hand, if we don't see a new variant develop, maybe we won't. I think that that's the uncertainty that we have to convey to everyone and make clear that we've got to prepare for the worst and hope for the best.

The virus is not done with us yet. We are going to have an ongoing pandemic with this virus for some time now.

I think there was an important event in recent weeks that should have been a clarion call to the world of what we're up against: Taiwan announced it was no longer going to maintain its zero-Covid policy. The Omicron subvariant is like the wind -- you can deflect it, but you can't stop it.

Taiwan acknowledged that it can't control Omicron. So, we have to understand that we're now living with this virus, and no one has the perfect plan to get us out of it.

For the past two years, if I had a nickel for every time someone said to me, "Well, if we just did it like China or we did it like Taiwan, we would control this."

And look what's happened to each of those countries. Over time, no one in the world had the perfect solution for controlling this virus.

President Xi Jinping of China is maintaining his zero-Covid policy: Is he trying to show the power of the Chinese government to suppress this virus? Well, if that's the case, it sure backfired. Look what's happened in Shanghai. They locked down. They started to let up. And now they're shutting down again. China is a clear example of what won't work.

At the same time, you can't let this thing just go willy-nilly, and that's why vaccinations still remain so key. Getting antiviral drugs to those at highest risk for severe disease is also a really important aspect of our response.

BERGEN: What about vaccinations for the under 5s?

OSTERHOLM: I think that we should have them available. We have had major transmission of Covid in schools and day cares to parents, grandparents and other family contacts. So if you can cut down transmission in that group, it would likely have a knock-on effect. Remember that more than 400 children in the US under 5 years of age have died from Covid.

I realize there are a lot of parents of younger kids who say, "Oh, this is an experiment. I'm going to wait. My child is not that high risk of having it happen," and so I think even if a vaccine is approved in the next weeks, by the time school starts again in the fall, you'll see only very limited uptake.

BERGEN: Should people get the second booster if they're over 50 or are immunocompromised?

OSTERHOLM: The whole issue with boosters is going to be a challenge. What is it going to look like in October and November for those people who had their booster in March and April? I don't know.

The data suggests that people who were vaccinated with mRNA vaccines such as Pfizer and Moderna are going to need perpetual boosters, but this is going to be a huge challenge. Look at the issue right now with the third dose. The last data I saw, only 46% of people that had two doses got the third dose.

These are not vaccine-hesitant people. We need to better understand why they haven't gotten a third dose and ask ourselves whether uptake is going to get any better with a fourth dose. And what if we need a fifth dose?

And so I think that we have to take a step back right now and ask ourselves what can we accomplish with our mRNA vaccines, and be prepared for the possibility of a brand-new variant. Will we set ourselves back if we adopt an Omicron-specific vaccine, only for a different new variant to emerge?

We're very fortunate that the number of deaths per number of cases has decreased dramatically, but if you are in high risk, if you're over 65, you're overweight, you have diabetes, you have hypertension, these are all risk factors for severe disease. Vaccinations will surely help provide some critical protection, but I know way too many of my younger, otherwise healthy colleagues right now who are at home, sick for seven to 10 days even though they have been fully vaccinated with the booster dose.

I think the additional challenge right now is that people want to get out and live their lives like they did before the pandemic. But my question is, what do you do if we see a new variant? Will people be willing to adapt, isolate or distance themselves again? I don't think they will at this point.

BERGEN: Did you go to the White House Correspondents' dinner?

OSTERHOLM: I wasn't invited, and if I had been, I would not have gone. I've not been out in indoor public places like that.

BERGEN: Was the White House Correspondents' dinner an accident waiting to happen?

OSTERHOLM: Oh, absolutely, it was. And it's not just the Correspondents' Dinner. It's all the parties around it.

BERGEN: What's surprised you about the last couple of years?

OSTERHOLM: I'm surprised that more people won't admit that they're surprised.

We need to stay humble and realize this virus is throwing 210-mph curveballs at us, day after day. Who would have thought that Omicron, which wreaked havoc in December, January and early February, would rear its ugly head and come back at us with all these subvariants?

We haven't seen that biologic array of subvariants before. We didn't see them with Delta or Alpha, Gamma and Beta. What we're learning is that this virus really has a very dynamic ongoing evolutionary process. And what does that mean relative to the future? That's a trillion-dollar question I can't answer.

BERGEN: Speaking of the future, how well-positioned are we for the next pandemic?

OSTERHOLM: We're not. We've suffered numerous setbacks, and our society's trust in public health is probably at its lowest level since my career began 47 years ago. And public health has relied not just on the volunteerism and goodwill of the people but the ability for the public to understand why we're sometimes asking them to do difficult things to save lives and to reduce the impact of this illness. Trust in the CDC as an organization has eroded significantly during this pandemic.

Second, at a time when we need more support for better vaccines and more drugs, we have a Congress that is debating whether or not to provide more funding.

Also, 500,000 people in the United States have left the health care field since the pandemic began, in large part due to burnout. We're shorter-staffed now than we've ever been in my career.

And there is going to be a long tail to this pandemic that we still have not fully appreciated, given that so many people have long Covid. I think our response to this issue in the United States has been really lacking.

From a public health standpoint, I'm not seeing any systematic changes that would suggest we're in better shape to face future pandemics. Our health care systems have done little to reform themselves around the world.

We still have all the challenges of low vaccination rates in the low- and middle-income countries. What does that mean? What happens if we need to vaccinate the world for a new avian influenza virus that becomes the next influenza pandemic virus?

Get our free weekly newsletter

Sign up for CNN Opinion's newsletter.

Join us on Twitter and Facebook

BERGEN: Isn't the CDC setting up some kind of early warning system?

OSTERHOLM: Yes, but if you have a virus that is highly infectious early on even before symptom onset, you've already lost control of virus transmission. All you can do is try to contain the impact globally. Think about what happened with Omicron and what we saw happening in South Africa after scientists there sounded the alarm. Countries responded by issuing travel bans against South Africans.

It turns out that wastewater surveillance retrospectively found the Omicron variant circulating in New York City before South Africa had announced its emergence. It was already around the world before we even knew it existed.

That doesn't mean you give up. What it says is you've got to be prepared. If you can't prevent the fires from happening, you've got to have a good fire department. And what we don't know yet is how would we make new vaccines for the next bad bug. We were fortunate with the mRNA vaccines that saved millions of lives. That may not work for the next pandemic.

Comments

Post a Comment